As-Vijvers 2018

Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, The Missing Miniatures of the Hours of Louis Quarré, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, vol. 10, iss. 1, 2018

Several dispersed miniatures are here identified as belonging to the Hours of Louis Quarré (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Douce 311). The original decorative program of the Quarré Hours is analyzed and the cuttings traced thus far are reintegrated into the manuscript. The Quarré Hours, which was probably produced in two stages, is situated in the oeuvre of the Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian. The provenances of the parent manuscript and cuttings are reconstructed in an attempt to determine when the Quarré Hours lost its miniatures.

1

On April 5, 1832, the antiquary and collector Francis Douce (1757–1834) attained a “beautiful horae at Hurd’s sale,” as he described the newest acquisition in his “Collecta” (notebooks).1 The price he paid for the volume, which is currently known as the Hours of Louis Quarré, was the highest that Douce is recorded as having spent on a manuscript. An inheritance received in 1827, after several years of legal wrangling, had finally allowed him to buy the finest manuscripts that came on the market, even though he remained very price conscious throughout his life.2 On his death in 1834, all of Douce’s manuscripts, printed books, coins, and prints were transferred to the Bodleian Library. During the following years, the library produced a printed catalogue with concise descriptions.3 In the 1897 Summary Catalogue, the Bodleian’s librarian, Falconer Madan, wrote that Ms Douce 311 probably lacked eight miniatures: “leaves presumably bearing miniatures are lost after foll. 33, 52, 55, 67, 76, 78, 80, 82, and perhaps elsewhere.”4 It is likely that Francis Douce—who was Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum for several years—had been aware of the missing miniatures. This fact clearly did not hold him back from spending a lot of money on the beautiful manuscript. When leafing through its pages, did he ever consider the possibility that the miniatures taken from his manuscript might still be extant?

2

The Print Room of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam keeps a Crucifixion miniature that has an unusually tall and narrow format (fig. 1).5 In 1948, Otto Pächt established a link between this Crucifixion and four miniatures formerly in the collection of John Rushout, Lord Northwick (1769–1859).6 Objects from the Northwick collection were sold in 1928 by Sotheby’s in London and the auction catalogue contains reproductions of the four miniatures: the Visitation, the Annunciation to the Shepherds, the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, and the Elevation of the Host. They all have the same tall format and the indicated dimensions (165 x 90 mm) are nearly identical to those of the Amsterdam Crucifixion (166 x 98 mm).7 All five miniatures have been deprived of their border decorations in a similar manner. Pächt attributed the group of five cuttings to the “Master of the Quarré Hours” (see below). Despite this important stylistic observation, Pächt apparently did not consider the possibility that the cuttings may actually have been taken from the Quarré Hours.8

3

A search for the present whereabouts of the miniatures from the 1928 catalogue made clear that their wanderings could be traced in more recent auction and collection catalogues. In 1992, William Voelke and Roger Wieck had added a sixth miniature to the group, an Adoration of the Magi then in the Breslauer collection.9 Although it was acknowledged in these catalogues (both before and after 1992) that the cuttings probably derived from one manuscript, and although they were stylistically linked to the Hours of Louis Quarré, the possibility that the Bodleian manuscript might be their parent manuscript was never raised, perhaps because the Quarré Hours manuscript had never been the subject of a comprehensive study.

4

When I looked at the reproductions from the Hours of Louis Quarré available on the website of the Bodleian Library,10 I noticed that its miniatures were not only in the same style as the cuttings but also had the same tall and narrow format. Judging from the website, the Quarré Hours seemed to include only an Annunciation and a Nativity, whereas—given the numerous other illustrations—one would expect a full Infancy cycle. The group of six cuttings actually contained four Infancy scenes (the Visitation, the Annunciation to the Shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Rest on the Flight into Egypt). The Rijksmuseum Crucifixion would fit a book of hours as well. Only one of the cuttings showed a less generic subject: the Elevation of the Host during Mass. In order to determine whether the website contained all of the miniatures in the Quarré Hours, I asked Margaret Goehring—who had previously published an article on the manuscript11—for a description of the volume. Building on this description, I was able to make a preliminary reconstruction of the decorative program of the Quarré Hours, in which all six cuttings could be integrated.12 Subsequent examination of the original manuscript in the Bodleian Library13 made clear that the sizes of the cuttings were the same as the miniatures (ca. 163–70 x 89–98 mm) that still remained in the Quarré Hours, which is itself quite large (237 x 178 mm).14 Unfortunately, the extracted miniatures left barely any traces of their existence. No stubs are visible and the tight binding of the manuscript does not permit investigation of the structure of the gatherings.15 However, when the Quarré Hours was rebound in the early nineteenth century, the edges of the book block had to be trimmed. In doing this, the binder cut through the numbers of an existing foliation, which dated from the late seventeenth or eighteenth century. This foliation, in brown ink, does not agree with the current, late-nineteenth century foliation, which is in pencil.16 The earlier ink foliation omits one number in every place where a miniature is likely missing. This leads to the conclusion that the six cuttings belonged to the original program of illumination. Moreover, the ink foliation makes clear that several other folios are lacking as well.

5

Pächt’s designation of the illuminator as “Master of the Quarré Hours” has not been maintained in later scholarship and the Hours of Louis Quarré is now generally attributed to the Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian.17 This illuminator, also called the Maximilian Master, was probably active in Ghent between the late 1470s and ca. 1520. Although the evidence is circumstantial, he might be identified with Alexander Bening (d. 1519), the father of the celebrated Simon Bening. The corpus of manuscripts associated with the Maximilian Master cannot be attributed to one main artist, however. The manuscripts within this large and complex group show considerable differences in terms of style and quality, while at the same time they share the same compositions, many of which originated in the 1470s. They also share similar figure types with large heads and strong facial features modeled in gray and pink. The subdued palette of the earlier manuscripts gradually shifted toward brighter colors.18 The Maximilian Master’s workshop probably involved a number of collaborators. Among these illuminators only a few with a more distinctive style have been singled out and only one of them has received a name of his own, the Master of the Munich Annunciation.19 For the purpose of this article, I will use the name Maximilian Master as a generic term for the style. I will also distinguish several hands within the Quarré Hours, although relating these to other manuscripts within the Maximilian Master’s oeuvre goes beyond the scope of this article.

6

In the following sections of this article, I will provide an overview of the original illustration program of the Hours of Louis Quarré into which the six cuttings will be integrated (see the Appendix). The two largest devotional cycles in the Quarré Hours are the Weekday Hours and the Hours of the Virgin, which will be presented first. In the following section I will discuss the Penitential Psalms, the Office of the Dead, and a number of other texts, some of which also lack either illustrations or text leaves or both. The calendar of the manuscript, which was replaced at an early date, as well as a few other changes suggest that the manuscripts was executed in two stages. The explanation for these alterations may be found in a change of the intended owner of the manuscript. I will present what is known about the original patron and use stylistic evidence to situate the manuscript in the oeuvre of the Maximilian Master. In the final section of this article, I will attempt to reconstruct how the Quarré Hours lost its miniatures.

The Weekday Hours

7

The Hours of Louis Quarré was conceived as a de luxe book of hours. After the calendar, the manuscript opens with the Weekday Hours: a series of offices tied to the days of the week, from Sunday to Saturday. This devotional cycle incorporates short versions of the well-known Hours of the Cross, the Hours of the Holy Spirit, and the Mass of the Virgin, which in an average book of hours would appear as separate texts. Indeed a full office for the Weekday Hours appears in only a few lavish books of hours of the 1470s–90s. One of these is the Hours of Isabella the Catholic in Cleveland, which, like the Quarré Hours, was illuminated by the Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian. In addition to the miniatures by the Maximilian Master (who supervised the illumination) the Cleveland Isabella Hours further includes one miniature by Gerard David, two miniatures by the Master of James IV of Scotland (possibly Gerard Horenbout), and four miniatures by the Master of the Prayer Books of around 1500. The manuscript is generally dated between ca. 1495–97 and 1504.20 As we will see, the Isabella Hours provides a valuable reference point for the missing miniatures of the Quarré Hours, even though its selection of texts and illustrations is not identical.

8

The Weekday Hours begin with the Sunday Hours of the Trinity, which still has its full-page miniature of God the Father holding the dead Christ in his lap, with the dove of the Holy Spirit on his shoulder (fol. 9v; fig. 2). The composition derives from Hugo van der Goes’s Trinity panel from the Edward Bonkil altarpiece made between 1473 and ca. 1478.21 In the early 1480s, copies of the Goes Trinity appeared in book illumination, either of the entire panel or of the single figure of Christ, which was transformed into a half-length Man of Sorrows.22 The Maximilian Master, however, pushed the entire group closer to the picture plane, with Christ shown in three-quarter length. In doing so, he succeeded in preserving the emotional impact of the Man of Sorrows version without losing the Trinity theme as required by the text of the office.

9

The Trinity was painted by the main artist of the Quarré Hours, called here “hand A.” His style is characterized by sophisticated gray, red, and white hatchings in the top paint layers of the faces, curling hairs, myriads of tiny gold hatchings on folds, and carefully executed backgrounds. In the Trinity, the figures in the heavenly realm have each been painstakingly rendered. The soft colors of the strewn-flower borders surrounding this opening match with the pastels used in the miniature. Although the two borders do not contain the same flowers, their colors and the rhythmic arrangement of smaller and larger species have been assiduously adjusted to each other.

10

The Sunday Hours of the Trinity is followed by a prayer to the individual persons of the Trinity (fols. 14r–15r). The ink foliation lacks one number here, suggesting that a full-page miniature is missing. This does not seem mandatory, however, because God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are depicted in three smaller miniatures within the text area. The figure of the Father blessing from heaven (fol. 14r) was taken from a composition for the Souls of the Saved Brought to Heaven, which accompanies the Monday Hours of the Dead in other manuscripts associated with the Maximilian Master’s workshop.23 The three smaller images were painted by another artist (“hand C”), who carefully finished the figures with modeling in gray but whose hand lacks the refinement of the main artist’s work.

11

The Monday Hours of the Dead is accompanied by a Raising of Lazarus with figures in half-length (fol. 16v; fig. 3). Probably around 1490, the Maximilian Master acquired a series of miniatures by the Valenciennes painter and illuminator Simon Marmion (d. 1489), which he incorporated in a book of hours known as La Flora (see fig. 13).24 The Marmion miniatures, which included eighteen dramatic close-up compositions, were also meticulously copied by the Maximilian Master and his workshop for application in other manuscripts, including the Quarré Hours. The large heads of the protagonists in the Raising of Lazarus, with crisp curls in their hair, appear to be in a more graphic style than the Trinity, but the modeling of the flesh tones and the folds is in fact quite similar.

12

Four-sided flower-and-acanthus borders frame the entire opening, with a vignette of a wrestling wild man and monkey—near the gutter of the recto page—that is derived from the drollery scenes in the Hours of Engelbert of Nassau.25 The face of the wild man resembles that of Christ in the small miniature illustrating the prayer to the Son of God on fol. 14v, suggesting these were done by the same artist, “hand C.”

13

The Tuesday Hours of the Holy Spirit opens with a full-page Pentecost (fol. 21v), in a style that—despite the smaller sizes of the figures—is midway between that of the Trinity and the Raising of Lazarus. This suggests that all three miniatures might have been done by “hand A.” As he did for the Trinity, the Maximilian Master adopted a model from the circle of the Ghent Associates, the pattern for which appeared in the 1470s or early 1480s.26 Although the composition was adjusted to the narrower format of the Quarré Hours, the individual figures and their grouping remain remarkably close to the Ghent Associates model, while the dark ambiguous background space was replaced by a clear wall. An intermediate version is included in the Hours of Katherine Bray, which is generally dated ca. 1490.27 Around 1500, in the Mayer van den Bergh Breviary, the Maximilian Master created a background view into the adjacent parts of the church, which—along with the addition of extra figures—helped to define the space in which the sacred event took place.28

14

A border of precisely rendered pilgrims’ badges frames the Quarré Pentecost.29 Even the imaginary needle by which the Veronica image is fastened onto the parchment is continued in paint on the recto side. The flower-and-acanthus border facing Pentecost has a bright blue ground, which is in harmony with the blue of Mary’s mantle, while an orange pimpernel is strategically placed at the same height as the orange sleeve of the apostle behind her.

15

The Wednesday Hours of All Saints is illustrated accordingly with All Saints (fol. 25v; fig. 4). This miniature, which is even taller than the previous ones, has a multifigure composition and is in a soft, painterly style, with nothing of the graphic elements present in the Raising of Lazarus. The figures are more puppetlike than those in the Trinity, featuring bulbous noses when seen in profile. The heavenly spheres are treated as a decorative pattern instead of as moving figures. The miniature may be attributed to an associate of the Maximilian Master, called “hand B” within the context of the Quarré Hours.

16

The All Saints composition follows a model in use by the early 1480s, when it appeared as a grisaille miniature in the Berlin Hours of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian, accompanying a suffrage to All Saints.30 The gray, white, and gold tones of a grisaille model still permeate in the whites, light blue, and gold colors of the Quarré version, even though a strong blue and some red and green have been added. A nearly identical version, but in full color, appears in the Isabella Hours by the Maximilian Master.31

17

The Thursday Hours of the Sacrament features an unusual composition of the Last Supper (fol. 29v; fig. 5), with Christ at the head of a long foreshortened table that stretches from the front to the back of a large room. This was copied from a model by the Vienna Master of Mary of Burgundy: nearly the same composition appears in the Breviary of Margaret of York at St. John’s College, which dates from ca. 1475–1480.32 The Maximilian Master (that is, “hand A” in the Quarré Hours) enlarged the four main figures so as to emphasize the dramatic moment in which Christ gives the host to a kneeling Judas as the onlooking apostles realize the latter would betray them. The square format of the miniature in Margaret’s breviary may explain why the Quarré Last Supper is wider than the other miniatures.33

18

The Last Supper is surrounded by splendid enameled flowers on a black ground.34 The grayish blues in the enamels and the miniature are reflected in the landscape of the facing historiated border, which contains people seated in boats (fol. 30r). As if part of a May boating party, the company to the right is drinking and making music in a boat decorated with green leaves. The people in the left boat, however, appear to pay attention to the sacred communion taking place in the miniature, while in the background people are gathering manna in an obvious reference to the Holy Sacrament. Despite the apparent discrepancy of the festive boat and the Eucharistic theme, religious songs of the period contrasted the temporary joy of the secular maypole with the eternal fruit of the tree of the cross. In the context of the Hours of the Holy Sacrament, both the host and Christ could be interpreted as the fruit of the cross.35 The border illustration was painted by the same associate (“hand B”) who did the All Saints miniature in the Wednesday Hours.

19

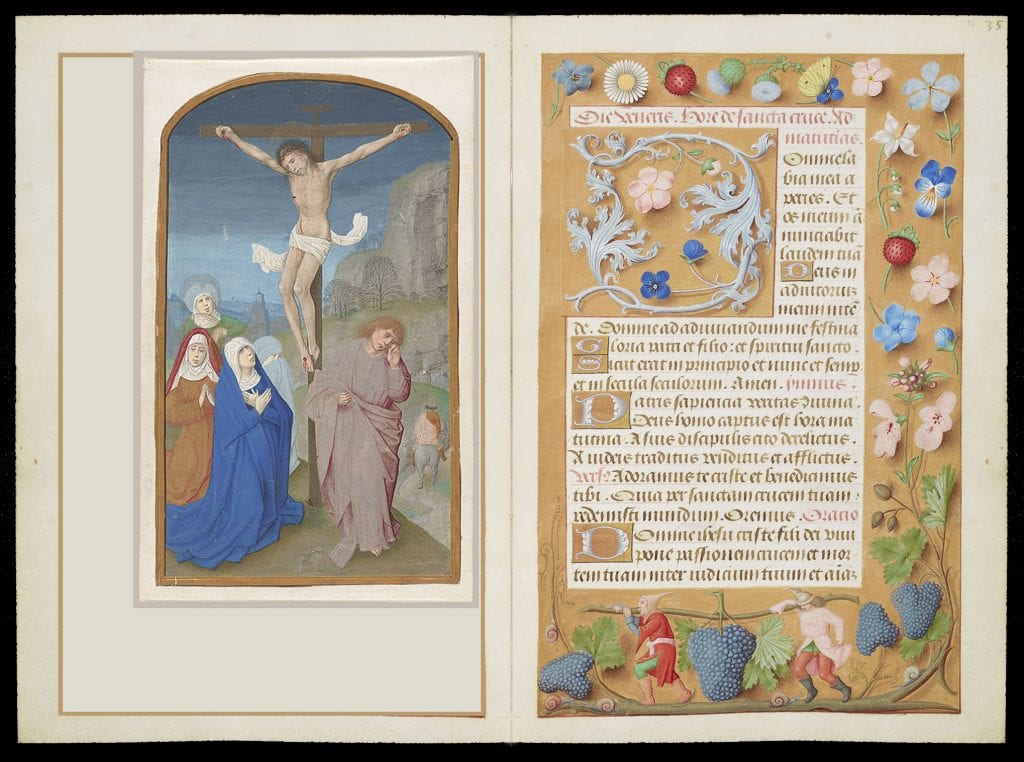

The Friday Hours of the Cross has no miniature facing the incipit page. Given the decorative program of the Quarré Hours, one would expect a full-page miniature here as well. Checking the ink foliation makes clear that 34 is omitted. We can now imaginarily insert the first missing miniature: the Crucifixion in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 6). The earliest known owner of this cutting, which was not mentioned in the Northwick sale, was a “Miss E. M. Ranshaw” of London. When her collection was posthumously sold on February 9, 1943,36 it must have been acquired by Dr. and Mrs. Francis S. Springell, Portinscale (Cumbria, Lake District, U.K.), because the Crucifixion was described as coming from the Ranshaw collection when it resurfaced at the Springell sale on June 28, 1962.37 At this auction, which mainly contained Italian Old Master drawings from the Springell collection, the miniature was purchased by the Rijksmuseum as a refined example of the last flowering of Flemish illumination.38

20

The Crucifixion strongly resembles the Pentecost of the Quarré Hours in its serene mood and subdued colors. Although the protagonists are painted in the foreground, the soldiers marching away into the background of both miniatures, diminishing in height as they round the hills, suggest the Maximilian Master used a model from the Vienna Master of Mary of Burgundy or the Ghent Associates group. A nearly identical composition is included in the London Hastings Hours, which must date from before 1483 and has been associated with the Maximilian Master’s early style, before Marmion’s half-lengths entered the stage.39 Parallel to the Quarré All Saints, the Isabella Hours contains a close duplicate, executed in brighter colors.40 The incipit page of the Friday Hours is marked by a strewn-flower border containing the Old Testament prefiguration Two Men Returning from Canaan with Grapes (fol. 34r; fig. 6; probably by “hand B”).41

21

The Friday Hours of the Cross is followed by the Passion of Christ according to Saint John, which has a nine-line miniature of the Betrayal and Arrest of Christ (fol. 39r), based on a model that goes back to the Ghent Associates.42 The use of gold-and-brown grisaille suited a night scene such as the encounter of Christ and the soldiers on the Mount of Olives. The Isabella Hours contains a nearly identical composition in semigrisaille, which is used as a half-page miniature accompanying Prime of the Long Hours of the Cross for Friday.43

22

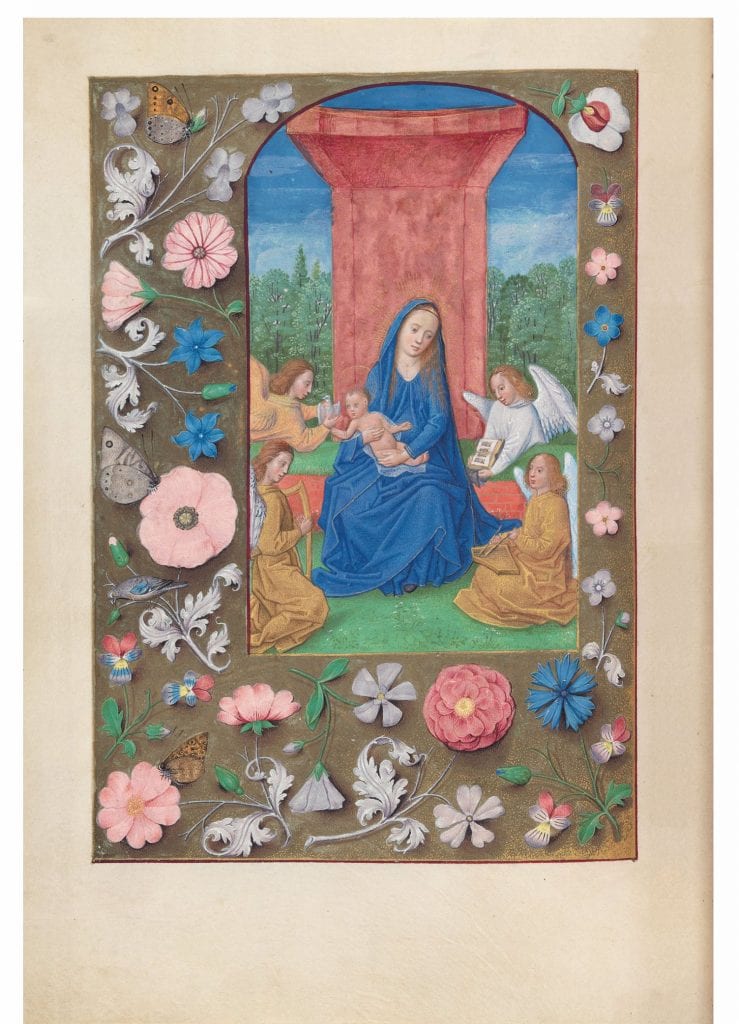

The Saturday Hours of the Virgin has retained its Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels (fol. 46v; fig. 7). Enthroned on a grassy bank and backed by a cloth of honor, the Virgin and Child are in the company of four angels, who play with the Christ Child and make music. This composition appears in at least two other manuscripts from the Maximilian Master’s workshop: the Hours of Katherine Bray and the Isabella Hours.44 Whereas the white robes of the Quarré angels still reflect the grisaille figures of the Bray Hours, the Isabella Hours version sparkles with color (fig. 8). The strong presence of the Quarré Virgin suggests the miniature might have been painted by “hand A.” The gold-brocaded backdrop is seamed with borders embroidered with letters. Although those on the left do not seem to form words, those on the right-hand side read “monstra te esse [matrem],” a phrase from the well-known Marian hymn Ave maris stella.

23

The Saturday Mass of the Virgin (fol. 47r) is without illustration, and because the ink foliation (by now running several numbers ahead) proceeds from 51 to 53, it is clear that another full-page miniature was once inserted at this point. Choosing from the extant cuttings, the Elevation of the Host may be placed here. This miniature was among the four cuttings from the Northwick collection in the 1928 Sotheby’s auction. Although it resurfaced at Christie’s in 1989 (under the erroneous title Mass of Saint Gregory), it once again submerged into a private collection after the sale.45

24

The Elevation of the Host would be an appropriate theme for the Saturday Mass of the Virgin, even though the text is more commonly accompanied by a Virgin and Child. In the Quarré Hours, another image was needed because a Madonna had already been used at the office proper. A thematic parallel for the Elevation of the Host appears in the Isabella Hours, which features a Celebration of Mass at the Saturday Mass of the Virgin. As mentioned above, the Isabella Hours was produced by the Maximilian Master and workshop; however, its Celebration of Mass is one of only two miniatures supplied by the Master of James IV of Scotland (Gerard Horenbout). The latter used an entirely different design than the illuminator (probably “hand B”) who painted the Elevation of the Host taken from the Quarré Hours.46 Instead, the cutting’s composition follows a model from the Voustre Demeure Hours, which has been attributed to the Vienna Master of Mary of Burgundy and his workshop and probably dates from ca. 1475–80.47

25

Two of the six extant cuttings from the Quarré Hours have now been reintegrated into the manuscript. For the other four, we have to turn to the devotional cycle illustrating the Hours of the Virgin.

The Hours of the Virgin

26

A second pictorial sequence in the Quarré Hours accompanies the Hours of the Virgin, which originally must have had an Infancy cycle of eight full-page miniatures: at Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline and the Office for Advent. Only three of these are in the book, four are included among the six cuttings that have currently been identified, and one has vanished without a trace.

27

Matins The opening miniature, the Annunciation at Matins, is still in the Quarré Hours (fol. 59v; fig. 9). This is the first of several close-up compositions, which—like the Raising of Lazarus discussed above—show the influence of Marmion’s La Flora series. The Quarré illuminator (“hand A”) did not place the figures as rigorously close to the picture plane as Marmion had done, and the tall format of the Quarré miniatures forced him to show a high-vaulted church instead of an intimate chapel as suggested in Marmion’s version.48

28

Lauds The Visitation meant for Lauds of the Virgin was among the miniatures in the 1928 Northwick sale, after which it disappeared until it was purchased from Maggs for William S. Glazier (1907–1962) in September 1950 and deposited in the Morgan Library by the trustees of the Glazier collection in 1963 (fig. 10).49 Although the Visitation is a close-up composition, it is not a direct imitation of any La Flora miniature. Instead, the illuminator (possibly the same hand as the Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels) endeavored to adopt a model that was familiar to him to the new format. A nearly identical version, showing Elizabeth with the same Old Testament headdress, appears in Clm 28345, a book of hours at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich illuminated ca. 1495–1500 by the Maximilian Master’s workshop in collaboration with the Master of the Prayer Books of around 1500. The Master of the Munich Annunciation (the associate of the Maximilian Master mentioned in the introduction of this article) derives his name from the Annunciation in this book of hours. The Munich manuscript also contains two mounted-in miniatures by Simon Marmion, which were originally part of the pictorial series used in the La Flora Hours. A single miniature of Christ before Caiaphas now in Lisbon probably once belonged to the Munich Hours as well;50 it has recently been argued that the face of Christ in this miniature was painted by Gerard David.51

29

Prime The Nativity is still in place at Prime of the Hours of the Virgin (fol. 73v; fig. 11). Although the half-length figure of Mary hints at Marmion’s close-ups, the interior setting, the figure of Joseph (here entering the stable), and the heads of the shepherds looking through a window are in line with the London Hastings Hours and earlier Ghent Associates models.52 Once again, the Munich Hours contains a close counterpart for the Quarré composition (fig. 12).53 Despite the extensive use of gray in the flesh tones, the Nativity shows the soft modeling in the faces that heralds the Trinity and the Last Supper of the Quarré Hours. The border around the text incipit, containing a dense pattern of gold and silver pilgrim’s bottles against a rose-colored background (fol. 74r), was also inspired by La Flora.

30

Terce Cuts are visible near the gutter of fols. 75 and 76 (partly repaired with paper), showing that a knife was used to extract the miniature for Terce, and the ink foliation jumps one number. The missing Annunciation to the Shepherds was illustrated in the Northwick catalogue of 1928, but it either remained unsold or was bought by a family member, because it was offered again in 1965, when the Northwick collection was dispersed.54 By 1992, the Shepherds was in the possession of the former Morgan Library director and president of the Association Internationale de Bibliophile Frederick B. Adams (1910–2001).55 After his death, the collection was auctioned in three parts at Sotheby’s London.56 Currently, the miniature is in a private collection.57

31

The composition of the Shepherds appears to have been inspired by La Flora in the prominent foreground figures and the rendering of the dark clouds in the sky, but the two miniatures are far from identical. The general landscape setting, the imbalance of the shepherds, and the flock of sheep are firmly rooted in Ghent Associates’ versions of the theme, augmented with a fashionable striped garment possibly inspired by a panel painting.58 The faces of the shepherds (albeit slightly grotesque), as well as the careful rendering of the trees in the background, find their closest counterparts in the Raising of Lazarus of the Quarré Hours.

32

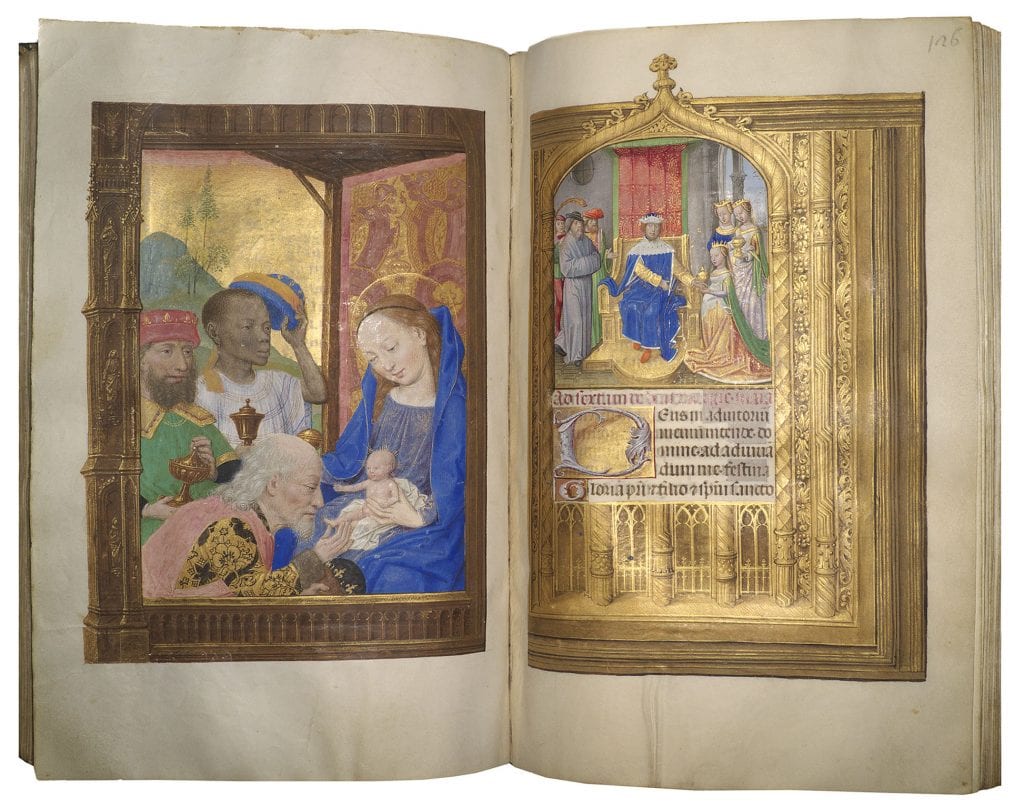

Sext The Adoration of the Magi, which should face Sext, had already been separated from the other four miniatures in the nineteenth century. The miniature became the property of Charles Scarisbrick (1801–1860), sheriff of Scarisbrick Hall and Wrightington, Lancashire (the region north of Liverpool and Manchester, in the western part of the United Kingdom), whose collection was dispersed in 1861.59 The Adoration of the Magi then appeared in the collection of the Paris painter Jean-François Gigoux (1806–1894), who amassed so many objects that from time to time he had to sell some. Possibly the miniature was included in one of these sales.60 In 1972 the Magi resurfaced at Sotheby’s, where it was purchased by the antiquarian bookseller and collector Bernard H. Breslauer (1918–2004). Twenty years later, in the winter of 1992–93, the miniature was shown in the Breslauer exhibition organized by the Morgan Library and Museum.61 When the Breslauer collection was auctioned by Christie’s New York in 2005, the miniature was acquired by a private collector.62

33

Like the Raising of Lazarus and the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi is a faithful copy of Marmion’s La Flora version (fig. 13). The golden sky was changed into a more naturalistic setting, and alterations were made to the color of the clothes and the gold brocade hanging.63 The details of Marmion’s half-length models required that the Maximilian Master (“hand A”) be particularly meticulous in his execution of the figures, whose faces are clearly delineated, down to the rosy blush on the cheeks.

34

None There is no miniature facing None of the Quarré Hours, even though number 88 in the ink foliation is lacking. The most likely theme here would have been the Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple; however, no such miniature was included in any of the auctions mentioned above nor has it surfaced in another collection. It might still exist, but its present whereabouts are unknown.

35

Vespers The miniature belonging at Vespers of the Quarré Hours, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, was in the Northwick sale of May 21, 1928, where it was bought by Frits Lugt (1884–1970). Soon afterward, on June 24, 1929, Lugt sold it to the collector Eduard August Veltman (1878–1965) in Bloemendaal, The Netherlands, but on April 13, 1938, he bought the cutting back. Although the miniature was stolen during the Second World War, it was returned afterward, and in 1947, the leaf, along with the rest of the Lugt collection, was transferred to the Fondation Custodia in Paris (fig. 14).64

36

The Rest on the Flight is an unusual theme for the Hours of the Virgin, which normally features the Flight into Egypt. The model for this composition is not known. The subject appears more frequently in the sixteenth century, with examples by Gerard David, Simon Bening, and the Master of Charles V.65 In fact, the Quarré cutting may have laid the foundations for the version included in the Prayer Book of James IV of Scotland (ca. 1502–3).66 Stylistically, the Rest on the Flight is on a par with the other miniatures in the Quarré Hours, although the folds are not rendered as three-dimensionally and the kneeling posture of Joseph is not very convincing.67 The luminous, sweet quality of the Virgin’s face and the figure of Joseph might be due to influence of the work of the Prayer Books Master. The tree at the upper left curiously bends with the frame of the miniature, which might be a reference to the apocryphal story of the bowing palm tree.

37

Compline The miniature for Compline, the Dormition of the Virgin, is still present in the Quarré Hours (fol. 87v; fig. 15). The composition, with the bed positioned diagonally, harks back to the Nassau Hours.68 By placing the bed at some distance from the frame, the illuminator made the apostles’ reactions the focus of the scene, but he lost the effect of a spacious room. The Dormition, which also has a broader frame than the other miniatures, was painted by a weaker hand, whose style is reminiscent of an associate of the Maximilian Master active in the Mayer van den Bergh Breviary.69

38

Office for Advent The Infancy cycle for the Hours of the Virgin often ends with a Coronation of the Virgin in Heaven or a related Marian image, such as the Madonna on the Crescent Crowned by Angels in the Isabella Hours.70 The Quarré Hours, however, contains a nine-line grisaille miniature showing the Entry into Jerusalem. Given the presence of this smaller miniature, it seems unlikely that the Office for Advent once featured a full-page image, which is confirmed by the fact that the ink foliation continues without interruption. The Entry into Jerusalem is not an obvious choice for the Office of Advent and may indicate that the genesis of the Quarré Hours was not as straightforward as it may seem at first sight.

Other Texts and More Missing Leaves

39

Only nine (out of sixteen) full-page miniatures from the Weekday Hours and the Hours of the Virgin are still bound into the manuscript. What else might be missing from the Quarré Hours?

40

The Penitential Psalms still have their Penitent David (fol. 102v), which is a reverse adaptation of La Flora. The Office of the Dead has a Funeral Mass (fol. 125v) based on a composition by Lieven van Lathem in the Trivulzio Hours, painted as early as ca. 1470, which also includes the kneeling male supplicant.71 The Funeral Mass is stylistically close to the Last Supper and the Nativity, while the half-length David strongly resembles the other verbatim La Flora copies in the Quarré Hours.

41

Prayers and suffrages In addition to the core texts mentioned thus far, the Quarré Hours contains miscellaneous prayers and suffrages, several of which were intended to have full-page miniatures as well. The Marian prayer “Obsecro te” has a four-sided historiated border featuring two children spinning tops next to a church portal (fol. 98r).72 The ink foliation omits one number, suggesting that a full-page Pièta or Lamentation at the Foot of the Cross was excised from here.73 The Seven Prayers of Saint Gregory (fol. 101r), surrounded by a border depicting a church interior, have clearly been deprived of a full-page Mass of Saint Gregory. Only a full-page Salvator Mundi, showing Christ (in half-length) blessing the world, was left untouched (fol. 122v).

42

Leafing through the Quarré Hours, one encounters several openings that appear to contain new incipits, but which do not have the appropriate level of decoration. One of these is fols. 44v–45r, the text of which ends on the verso followed by three blank lines, while the recto contains nothing more than a two-line decorated initial heading a short prayer. This invocation actually is the final prayer of an Office of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, implying that at least several leaves and either a full-page miniature or a smaller text miniature are missing.74 Remarkably, the ink foliation is not interrupted here, which means that the devotion of the Seven Sorrows was removed at an earlier stage than the other miniatures.

43

A similar case occurs on fols. 52v–53r. The verso has an explicit followed by eight blank lines, but the text on the recto begins with an undecorated capital letter. This text can be identified as the end of a Prayer to Mary to be said on Saturdays, interspersed with instructions in French.75 Between the missing lines from the prayer and its position after the Saturday Mass, it may be deduced that a folio with a nine- or ten-line miniature is missing. The ink foliation omits one number, implying that this leaf was extracted along with the other full-page miniatures.76

44

Moreover, the omission of 141 through 149 in the ink foliation (between fols. 124cv and 125r of the current foliation) suggests that a full gathering of eight leaves and a full-page miniature is lacking, but its contents can only be surmised.77 This gap is followed by the Office of the Dead, which is the final text in the Quarré Hours (fols. 125r–145r).

Changes in the Decorative Program

The (nearly) twenty full-page miniatures that the Quarré Hours once contained were supplemented with numerous smaller miniatures, most of which are still extant, illustrating the Gospel Lessons, suffrages and miscellaneous prayers. Although these images cannot be discussed individually within the scope of this article, it may be pointed out that they contain clues to a possible genesis of the Quarré Hours in two stages.

45

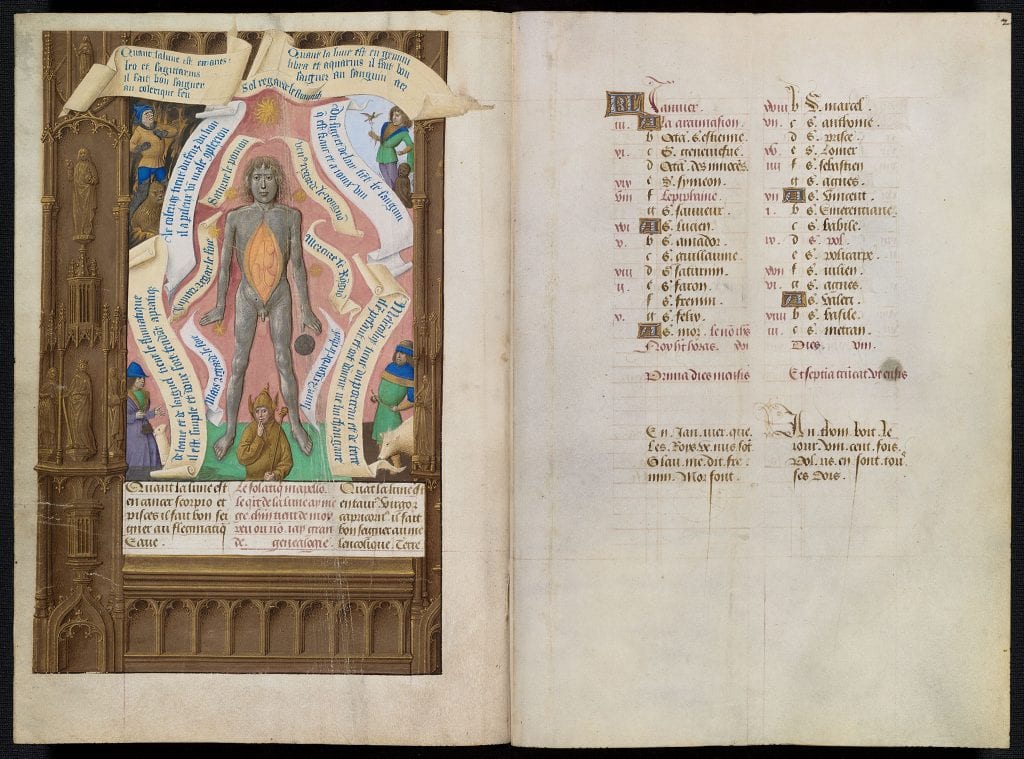

Changes to the original plan can be discerned right in the beginning of the book. The calendar must have been produced separately, because it was written by another hand than the main text, moreover, the parchment has a slightly different texture and thickness. The calendar is also unusual in that it is illustrated by a full-page Planetary Man (fol. 2v; fig. 16), which was painted by a separate artist (“hand D”).78 This zodiacal figure is preceded by an almanac for the period 1488–1508 (fols. 1v–2r) and followed by a calendar in French, including Cisiojanus verses (fols. 3r–8v).

46

The calendar image, the almanac, and Cisiojanus verses were probably copied from a printed book of hours issued by the Parisian printer Philippe Pigouchet.79 Further research might actually reveal which one of the numerous Pigouchet editions was available to the illuminators, because his various Horae contain two versions of the Planetary Man. The composition used in the Quarré Hours is apparently modeled after the earlier one of the two, which is still included in the edition of 1491–92,80 but by 1496–97 had been changed for a another version.81 Moreover, in the 1491–92 edition, the almanac appears in Latin on a two-page spread, whereas in the 1496–97 edition, the almanac is given in French and the information is condensed onto just one page. The Quarré Hours might reflect an intermediate stage between the 1491–92 and 1496–97 editions, because its almanac is written in French on a two-page spread (fols. 1v–2r). Between 1492 and 1496, Pigouchet published several editions of Horae, and if one of these actually turned out to have the characteristics described, a new terminus post quem for the production of the calendar might be defined.82

47

When leafing through the Quarré Hours, several of the miscellaneous prayers seem to have been inserted on ruling lines that were previously left blank, because the original text did not need a whole page. These prayers were possibly written by a another scribe, using blacker ink than the main scribe and producing a slightly larger script with firmer ascenders and descenders, along with subtle hairlines. Moreover, the decorated initials on these pages have been done in darker gold and brown tones, with more robust highlights. Examples include the Seven Words of Christ on the Cross (fol. 44r), which is embedded in the Weekday Hours; a Marian prayer (fol. 99v) and a Suffrage to Saint Anne (fol. 100r) inserted after the “Obsecro te” (fols. 98r–99v); and a Prayer to Christ on the Cross (fol. 101v) following the Seven Prayers of Saint Gregory (fols. 101r–101v).

48

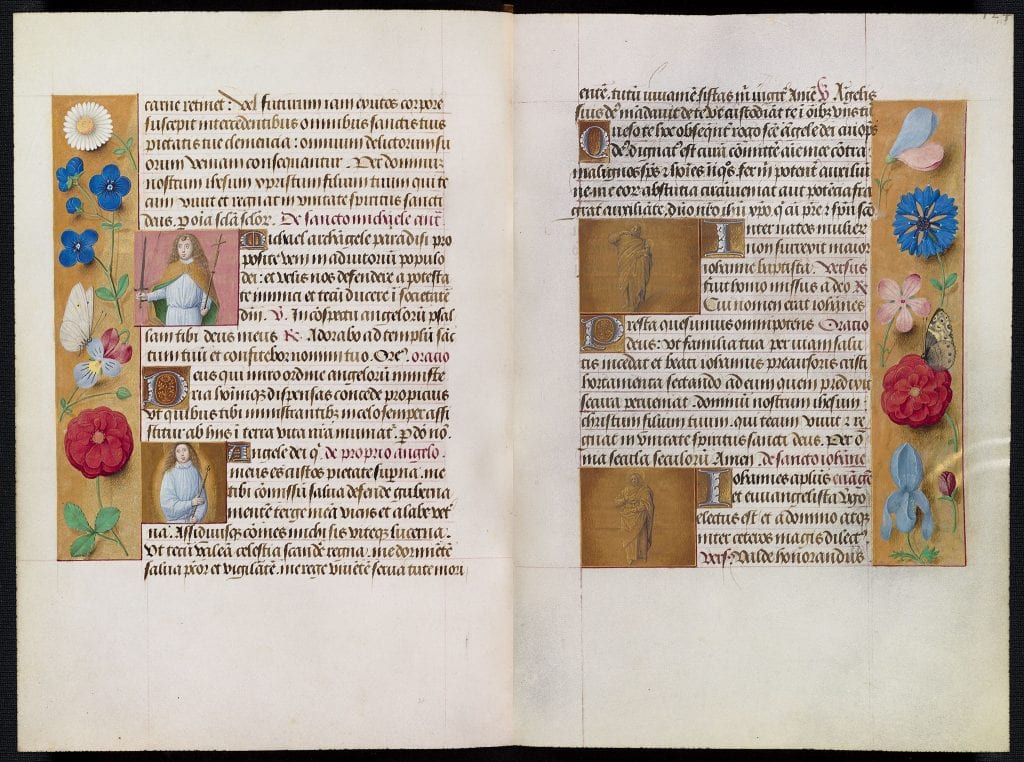

That these changes occurred at a stage when the border decoration had already been executed can be seen on fol. 113r. The suffrages to Saint Michael and the patron’s Guardian Angel (both on fol. 112v) were added on the final page of the Penitential Psalms (fols. 102v–112v). In order to fit those in, the scribe had to use extra lines at the bottom of fol. 112v and at the top of fol. 113r (fig. 17). He also erased the first six lines of fol. 113r, condensed the new writing, and put some letters over the painted border, but still ended up without enough space to include a rubric for the suffrage to Saint John the Baptist that followed and had already been written (fol. 113r). In this example, the second style in script and decorated initials can be clearly recognized, whereas on other pages the differences are too subtle to differentiate two hands.

49

The full-page Salvator Mundi, normally the first miniature in a book of hours, was moved to farther back in the book to accompany a prayer to Our Lord in French (written by yet another hand), which also appears in the 1491–92 Pigouchet Horae, with a nearly identical rubric.83 Did the new patron ask for both this prayer and the calendar with a printed book in hand?

50

When the second phase of production began, the grisaille miniatures illustrating the Gospel Lessons had already been executed (by hands “B” and “C”), but the text miniatures illustrating the miscellaneous prayers and suffrages were probably in various stages of completion. Apparently, both “hand B” and “hand C” of the original team, as well as “hand D” (the painter of the Planetary Man; see fig. 16), were involved in finishing the book. The latter excelled in the frontally depicted zodiacal figure, but in his smaller miniatures, the figures’s eyes often have a rather vacant stare (fol. 112v; fig. 17). This illuminator might even have had a hand in the Dormition, with its unwieldy rendering of faces. At the same time, the style of “hand D” is close enough to the other three illuminators to assume that he belonged to the entourage of the Maximilian Master. More research will be needed, however, to entangle all of the hands involved in the production of the Quarré Hours.

The Original Patron and the Date of the Quarré Hours

51

The observation that the manuscript was changed when the production was well underway, but prior to its completion, brings us to the patron of the manuscript. The Quarré Hours is named after two overpainted escutcheons, which have been identified as the coat of arms of Louis Quarré, seigneur de la Haye en Hainaut.84 Quarré was the son of a commander of lancers from the guard of Charles the Bold. In 1478, he married Barbara Croesinck (d. 1531), daughter of the lord of Benthuyse, by whom he had three children. The couple had themselves portrayed on the wings of a small triptych of the Virgin and Child meant for their home or family chapel.85

52

In 1482, Quarré became receveur général des finances of the Burgundian court in Malines under Philip the Handsome. On July 23, 1486, he was installed as treasurer of the Order of the Golden Fleece. In this position, he was responsible not only for the official documents of the order but also for the red gowns, textiles, ornaments, and books used during its ceremonies. From 1491 onward, Quarré combined this position with that of maître des comptes at the Court of Accounts of the duchy of Luxembourg in Brussels. Quarré, who was knighted in 1506, held the device “Louange a Dieu” (Glory to God). During his final years, Quarré suffered from health issues because of his “grand âge” (high age), but although he asked to be released of his task, he had to fulfill the position of treasurer until his death in 1520.86

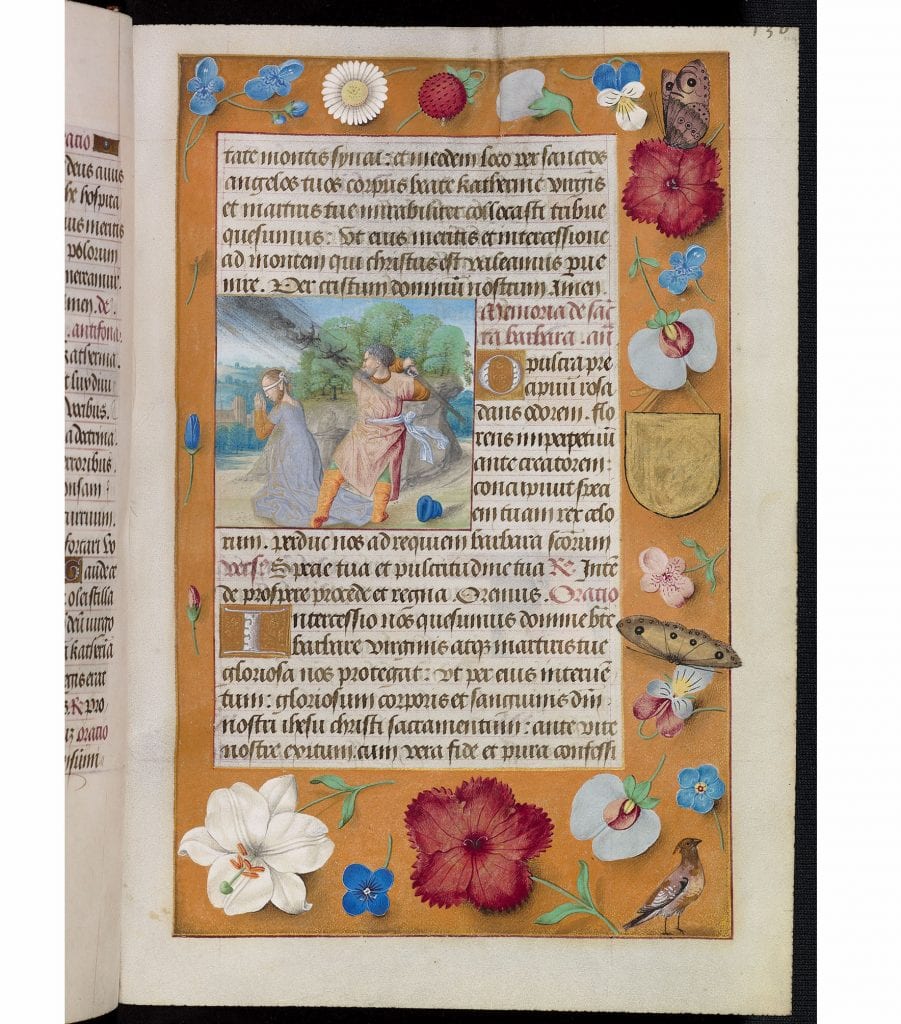

53

One of the two escutcheons in the Quarré Hours accompanies a suffrage to Saint Barbara (fol. 119r; fig. 18), which accords with the name of Quarré’s wife. This nine-line miniature, which follows a Ghent Associates model and belongs to the first campaign, was probably painted by “hand B” of the Quarré Hours. A second escutcheon hangs from the lower frame of the Salvator Mundi (fol. 122v). This image is usually associated with the popular “Salve sancta facies” prayer (a rhymed prayer to the face of Christ) and would normally appear as the first text after the calendar, which would have been an appropriate place for a coat of arms. This suggests that Louis Quarré may have been the first commissioner of the manuscript and that his armorials were overpainted during the second campaign, during which the Salvator was placed toward the end of the manuscript to adapt it for another, unidentified customer. Technical research into the escutcheons is warranted in order to confirm or deny these hypotheses.

54

What is known about Louis Quarré and his wife does not give many clues for dating the book of hours associated with them. The year of Quarré’s marriage to Barbara Croesinck (1478) is too early for the production of this manuscript, the birthdays of their children are unknown, and his financial positions seem not immediately relevant to either ordering a book of hours or abandoning the commission. Regarding the second patron, we can only say that he or she was probably a francophone. If a Pigouchet Horae could be traced that provided the model for the added calendar and prayers, we might have a terminus post quem for the second campaign (which probably followed directly upon the first), which would be particularly helpful in determining the chronology of the Maximilian Master’s oeuvre.

55

Dating the Quarré Hours must be done by comparison with other manuscripts from the Maximilian Master’s workshop. As we have seen, many of its compositions are firmly rooted in models of the 1470s and 1480s, without the kinds of adaptations seen in the Mayer van den Bergh Breviary (ca. 1500) and the Breviary of Eleanor of Portugal (ca. 1500–1510). The tall and narrow format of the Quarré miniatures,87 the tender colors in the full-page miniatures, the subtlety applied in matching the borders, and the use of camaïeu d’or for the text miniatures of the first campaign all seem to point to the early or mid-1490s, after the Bray Hours (ca. 1490) and before the Isabella Hours (ca. 1495/97–1504).

56

Although the decorative program of the Isabella Hours is closely related to that of the Quarré Hours, its miniatures are in brighter colors, and they already have the wider format favored in later manuscripts by the Maximilian Master’s workshop. The Isabella Hours was also produced by a different workshop member, who favored smaller figures, which he successfully integrated in their spatial settings at some distance from the frame (see fig. 8), whereas the illuminator of the Quarré Hours kept his figures close to the picture plane.

57

The manuscript that is stylistically closest to the Quarré Hours is the Munich Hours (ca. 1495–1500), with the Quarré Hours probably being the earlier of the two. Despite the obvious influence of Marmion’s La Flora series, the illuminator (“hand A”) did not yet fully adopt the close-up format. Instead, he reworked his own patterns with this new idea in mind. In the Munich Hours, the dramatic close-up format was extended to the Passion scenes, and frames like those of La Flora, with their relatively narrow outer and lower borders, depicting rather flat tracery, became the rule (see fig. 12).

58

The Munich Annunciation and several other close-up miniatures in both the Munich Hours and the Isabella Hours were attributed by Thomas Kren to the Master of the Munich Annunciation. Kren also offered the attractive suggestion that the Quarré Trinity, Raising of Lazarus, Annunciation, and Penitent David might be early works of the same illuminator, although they lack the robustness of those in the Munich Hours.88 Three of these miniatures are faithful copies of La Flora close-ups, which probably influenced the style of the illuminator. Within the context of the Quarré Hours (including the “reinserted” cuttings), there are gradual differences between the miniatures of “hand A,” depending on whether he painted one or more larger figures (e.g., the Nativity) or employed multifigure compositions (e.g., the Last Supper, Pentecost). The differences in facial and figural types might therefore stem from the variety of pattern sources rather than from different hands. More research will be needed to understand the relationships between the Quarré and the Munich Hours and the members of the Maximilian Master’s workshop involved in their production.

The Removal of the Miniatures

59

When Francis Douce bought the Quarré Hours in April 1832, at least nine, and possibly eleven, of its circa twenty full-page miniatures, as well as a number of text leaves, possibly up to two gatherings, were missing from the manuscript. Some of these texts and illustrations had been purloined before the ink foliation was done, but in the eighteenth century, the majority of the full-page mininatures were still present. Do we have any indications when the Quarré Hours was sacrificed for what were doubtlessly financially lucrative purposes?

60

As mentioned at the outset of this article, Douce acquired his “beautiful horae” at Hurd’s sale on April 5, 1832. The May issue of Gentleman’s Magazine noted that the sale of Mr. Hurd’s library had given “a fillip to the decline of bibliomania”: all the book collectors were present, the books brought good prices, and “Baron Denon’s Flemish missal” went to Mr. Douce.89 From Hurd’s sale catalogue, we learn that this “Chef D’Œuvre of Flemish Art” had been purchased by Mr. Hurd at the sale of the Reverend Mr. Williams’s Library and that it was known as “the celebrated Missal belonging to Baron Denon.”90

61

The information in Hurd’s catalogue was largely copied from the Williams sale catalogue, which specified the date, 1488 [taken from the almanac], the size, the number of folia, the number of large and smaller paintings and the kind of border decorations.91

62

As a young man, the Reverend Theodore Williams (1787–1876), vicar of Hendon (now a London suburb), collected a magnificent library, which he offered for sale in 1827.92 Since Williams had the majority of his books sumptuously bound, the sale catalogue descriptions pay particular attention to the bindings, describing that of the Quarré Hours as “a matchless specimen of the art, by Charles Lewis; it is of green morocco, tooled entirely over after a pattern of a book belonging to Diana of Poitiers.”93 The book’s clasps are of massive gold, richly chased, and the volume is enclosed in a box case covered with Venetian morocco. Both the binding and the box carry the initials and the arms of Theodore Williams.94

63

We may safely assume it was Charles Lewis (1786–1836), first listed as an independent binder in 1813 and one of the leading binders of his day, who took out the stubs of the detached miniatures and leaves as noted above. Lewis was the one who cut through the ink foliation, when he trimmed the edges of the Quarré Hours before they were gilded and gauffered.

64

How did Theodore Williams acquire the manuscript? Reading between the lines of his sale catalogue, he bought the volume from “Robert Heathcote, esq. a gentleman well known for his distinguished taste” and a considerable collector in his own right.95 According to the Williams catalogue, Heathcote purchased the manuscript from Baron Denon, who considered it “one of the gems in his collection.” Robert Heathcote (d. 1823) sold his entire library in 1808 but apparently remained active in the trade of manuscripts.96 In 1816, he brought the Peckover Hours (with miniatures by Jean Colombe, ca. 1490) from Paris to England.97 Did Robert Heathcote take Baron Denon’s “Missal” with him during the same trip?

65

The man known as Baron Denon was Dominique Vivant, baron Denon (1747–1825), draftsman, etcher, art dealer, archaeologist, Napoleon’s adviser on art plunder, and first director of the Louvre (1802–15).98 After the collapse of the Napoleonic empire, Denon retired as Louvre director. In 1816, therefore, he was able to spend more time on his own collection, where he found himself receiving mostly foreign visitors, the majority of them Englishmen.99

66

In his publication about his bibliographical tour through France in 1818, Thomas Dibdin mentioned that Denon’s house on the Quai Malaquais “is the rendezvous of all the English of any taste—who have respectable letters of introduction” and that he sometimes found that Denon’s principal rooms were “entirely filled by my countrymen and countrywomen.”100 Dibdin’s story suggests seeing Denon’s collection would certainly have been on Heathcote’s list when he visited Paris in 1816.

67

Moreover, Dibdin’s record makes clear that by 1818 the Quarré Hours was not in Denon’s collection anymore. After a detailed account of the rooms and the artworks therein, Dibdin remarks that Denon did not have a library, because “three or four pretty little illuminated volumes do not constitute a library.” From his detailed descriptions of the three “best samples of his collection of illuminated volumes” we can deduce that the Quarré Hours, if it were still there, would have belonged to this select group, but none of the descriptions matches the manuscript.101

68

Piecing the puzzle together, it may be proposed that Robert Heathcote acquired the Quarré Hours from Baron Denon in 1816 and transferred the manuscript to England. The question remains whether the Quarré Hours was still intact at this time. Only circumstantial evidence can be provided here, however, since five of the six cuttings have an early nineteenth century English provenance (the sixth, the Crucifixion, surfaced in 1943 in London), the most likely scenario seems that either Heathcote or an unknown intermediate owner was the person who victimized the beautiful Horae first admired by Baron Denon, and then—despite its missing miniatures—by Francis Douce.

Noten:

1The Douce Legacy: An Exhibition to Commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Bequest of Francis Douce (1757–1834) (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1984), 171.

2The Douce Legacy, 134, 137; see also A. N. L. Munby, Connoisseurs and Medieval Miniatures 1750–1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 35–56.

3 Catalogue of the Printed Books and Manuscripts Bequeathed by Francis Douce, Esq. to the Bodleian Library (Oxford: University Press, 1840), 54, no. cccxi.

4 Falconer Madan, Collections Received during the First Half of the 19th Century: Nos. 16670– 24330, 589–590 (no. 21885), vol. 4 of A Summary Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford . . . , ed. Richard W. Hunt (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1897).

5 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv. RP-T-1962-54; see Karel G. Boon, Netherlandish Drawings of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij, 1978), no. 11.

6 Otto Pächt, The Master of Mary of Burgundy (London: Faber and Faber, 1948), 60–61; see also Otto Pächt “The Master of Mary of Burgundy,” Burlington Magazine 85 no. 501 (December 1944): 300n16.

7 See Catalogue of Superb Illuminations from the Collection of the Late John, Lord Northwick . . . (London: Sotheby’s, May 21, 1928), lots 8–11. The sizes of the individual miniatures are given in the Appendix.

8 I would like to thank Anne Korteweg, who drew my attention to the Northwick cuttings during our visit to the Rijksmuseum and who encouraged me to publish my findings.

9 William M. Voelke and Roger S. Wieck, The Bernard H. Breslauer Collection of Manuscript Illuminations, exh. cat. (New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1992), 98–99, no. 21.

10 Images of Bodleian manuscripts are available at http://bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk:8180/luna/ servlet.

11 [ii] Margaret L. Goehring, “Artist or Style? A Consideration of the Master of the ‘Older’ Prayer Book of Maximilian I,” in Manuscript Studies in the Low Countries: Proceedings of the “Groninger Codicologendagen” in Friesland, 2002, ed. Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, Jos M. M. Hermans, and Gerda C. Huisman, vol. 3 of Boekhistorische Reeks (Groningen: Egbert Forsten and Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy, 2008).

12 I am very grateful to Margaret Goehring for her generosity, which allowed me to turn an idea into a research hypothesis.

13 I would like to thank Martin Kaufmann for his permission to study the Quarré Hours.

14 With the exception of the Crucifixion, I have not been able to measure the cuttings myself, but the literature is consistent on their size. As can be seen in the Appendix, the size of the extant miniatures varies within several millimeters (as it does in other manuscripts), which makes clear that the size of the cuttings is perfectly in line with those in the Quarré Hours.

15 Despite the presence of several catchwords, it proved impossible to determine (or reconstruct) the original structure of the gatherings, because not only are the quires sewn in the gutter, but threads are also zigzagged top-downward through the surface of the folios.

16 I thank Bruce Barker-Benfield for confirming the dating.

17 The eponymous manuscript is Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 1907.

18 Thomas Kren, “Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian,” in Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, exh. cat., ed. Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrick (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003), 190–91.

19 Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 319–20. Brigitte Dekeyzer, Herfsttij van de Vlaamse miniatuurkunst: Het Breviarium Mayer van den Bergh/Layers of Illusion: The Mayer van den Bergh Breviary (Ghent and Amsterdam: Ludion, 2004), 92, defined hands A to E in the Mayer van den Bergh Breviary, and Goehring, “Artist or Style?” 191–93, designated the Master of the London Hastings Hours.

20 Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256; Patrick M. de Winter, “A Book of Hours of Queen Isabel la Católica,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 67, no. 10 (December 1981); Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 358–61, no. 105; Lieve De Kesel, The Hours of Queen Isabella the Catholic: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund 1963.256 (Gütersloh: Faksimile Verlag, 2014); digitized at www.clevelandart.org/art/1963.256.

21 Oil on panel, Ghent, ca. 1473–78, Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland; Thomas Kren, “The Importance of Patterns in the Emergence of a New Style of Flemish Manuscript Illumination after 1470,” in Manuscripts in Transition: Recycling Manuscripts, Texts, and Images; Proceedings of the International Congress Held in Brussels (5–9 November 2002), ed. Brigitte Dekeyzer and Jan Van der Stock (Paris, Leuven, and Dudley, Mass.: Peeters, 2005), 357–58, ills. 1–3; Dekeyzer, Herfsttij van de Vlaamse miniatuurkunst, 151–56.

22 The Trinity appears in the Berlin Hours of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian: Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms 78 B 12 (fol. 13v), and in the Madrid Hours of William Lord Hastings: Madrid, Museo Lázaro-Galdiano, inv. 15503 (fol. 14v). The Man of Sorrows appears in Berlin (fol. 56v), Madrid (fol. 252v), and in the Hours of Katherine Bray: Lancashire, Stonyhurst College, Ms 60 (fol. 162v; by the Maximilian Master). For reproductions, see Gerard I. Lieftinck, Boekverluchters uit de omgeving van Maria van Bourgondië c. 1475–c. 1485 (Brussels: Paleis der Academiën, 1969), vol. 2, pls. 190, 165, 202, 204; Eberhard König, Das Berliner Stundenbuch der Maria von Burgund und Kaiser Maximilians(Lachen am Zürichsee: Coron, 1998), 44, fig. 119: Abb. 23–24.

23 London Hours of William Lord Hastings: London, British Library, Add. Ms 54782 (fol. 230v) and the Isabella Hours (fol. 24v); see Winter, “A Book of Hours of Queen Isabel la Católica,” 356: figs. 26–27, 396–97. For digitized British Library manuscripts, see https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/.

24 Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, Ms I.B.51; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 330–34, no. 93; Romeo De Maio, ed., Il Codice Flora: Una pinacoteca miniata nella Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli(Naples: Pironti, 1992); La Flora (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis), facsimile (Rome and Turin: De Agostini/UTET, 2008)].

25 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Mss Douce 219–220 (fol. 132v: the wrestling figures in the center); Jonathan J. G. Alexander, The Master of Mary of Burgundy: A Book of Hours for Engelbert of Nassau (New York: Braziller, 1970), pl. 108.

26 See, for example, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Douce 223 (fol. 29v), a book of hours connected with the Abbey of Saint Peter, Blandin, Ghent; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 188–89, no. 40, esp. note 9.

27 Lancashire, Stonyhurst College, Ms 60 (fol. 66v); see also Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 316–17, no. 88.

28 Antwerp, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, inv. 946 (fol. 318v); Dekeyzer, Herfsttij van de Vlaamse miniatuurkunst, 51, fig. 46. The simpler version, by a workshop member, in the Breviary of Eleanor of Portugal (New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms 52, fol. 181v) was probably based on the Quarré version; on this manuscript, see Margaret L. Goehring, “Exploring the Border: The Breviary of Eleanor of Portugal,” in Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative, Emotional, Physical, and Spatial Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art, ed. Sarah Blick and Laura D. Gelfand (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011), 1:123–48.

29 Hanneke van Asperen, Pelgrimstekens op perkament: Originele en nageschilderde bedevaartssouvenirs in religieuze boeken (ca 1450–ca 1530), Nijmeegse Kunsthistorische Studies 16 (Edam: Orange House, 2009), 200–203, 404–5, no. 23.

30 Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms 78 B 12 (fol. 330v); König, Das Berliner Stundenbuch der Maria von Burgund und Kaiser Maximilians, 100–101, fig.; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 183–86, no. 38.

31 Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256 (fol. 37v); Winter, “A Book of Hours of Queen Isabel la Católica,” 358–59 (figs. 31–32, 36), 396–97; De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 70, 146 fig. 45.

32 Cambridge, St. John’s College, Ms H. 13 (James no. 215) (fol. 57v); Paul Binski and Stella Panayotova, eds., The Cambridge Illuminations (London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2005), 134–36, no. 50 (illus.).

33 This miniature measures 172 x 99 mm instead of the average 165 x 90 mm.

34 A nearly identical border appears in the Mayer van den Bergh Breviary (fol. 259v).

35 Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, “Bloemen van betekenis: De interpretatie van de randversiering in Zuid-Nederlandse handschriften rond 1500,” in De Groene Middeleeuwen: Duizend jaar gebruik van planten (600–1600), ed. Linda IJpelaar and Claudine A. Chavannes-Mazel (Eindhoven: Lecturis, 2016), 259.

36 Catalogue of Early Printed Books: …Miniatures and Illuminations on Vellum…, auction cat. (London: Sotheby’s, 9 February 1943).

37 Catalogue of Important Old Master Drawings of the Italian School . . . and Thirteen Illuminations from Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts . . . , auction cat. (London: Sotheby’s, June 28, 1962), 37, lot 52. In 1959 the miniature had been included in an exhibition of the Springell collection.

38 Verslagen der Rijksverzamelingen van geschiedenis en kunst, vol. lxxxiv – 1962 (The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij- en uitgeverijbedrijf, 1964), 40.

39 London, British Library, Add. Ms 54782 (fol. 250v); Kren, “Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian”; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 192–93, no. 41.

40 Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256 (fol. 72v).

41 For the Crucifixion miniature and the incipit of the Friday Hours of the Cross in the Quarré Hours see also Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers and Anne S. Korteweg, Splendour of the Burgundian Netherlands: Southern Netherlandish Illuminated Manuscripts in Dutch Collections (Zwolle: WBooks, 2018)), 280-81, no. 75.

42 Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms 78 B 12 (fol. 114v); König, Das Berliner Stundenbuch der Maria von Burgund und Kaiser Maximilians, 62, fig.

43 Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256 (fol. 61r).

44 Bray Hours (fol. 45v), reproduced in De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 159, fig. 58.

45 Medieval and Illuminated Manuscripts, Valuable Printed Books, Autograph Letters and Manuscripts, auction cat. (London: Christie’s, December 6, 1989), 13, lot 6, with color pl.

46 De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 77; Michaela Krieger, Gerard Horenbout und der Meister Jakobs IV. von Schottland: Stilkritische Überlegungen zur flämischen Buchmalerei (Vienna, Cologne, and Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2012), 162–68.

47 The full-page miniatures of the Voustre Demeure Hours (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, Ms Vit. 25-5) are kept in an album in Berlin. See Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms 78 B 13 (fol. 16): Lieftinck, Boekverluchters, vol. 2, pl. 152. See also Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 143, 145n3.

48 The close-up version by the Master of the Munich Annunciation in the Munich Hours (see below) is a reinterpretation of Marmion’s model, in which Gabriel raises his right arm in announcement, a gesture favored in earlier manuscripts by the Ghent Associates circle and, later on, by Simon Bening. See Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 28345 (fol. 14v): De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 133, fig. 32.

49 See the curatorial files of the Morgan manuscript at http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=77493. The Glazier collection became a permanent gift to the Morgan in 1984.

50 Lisbon, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Ms. M. 18r: De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 132, fig. 31.

51 See note 48 above and Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 31821, no. 90; Lieve De Kesel, “Use and Reuse of Manuscripts and Miniatures: Observations on Pasted-in, Recycled and Removed Miniatures and Text Leaves in Some Late Medieval Flemish Illuminated Manuscripts Related to ‘La Flora,’” Bulletin du bibliophile (2011-1); De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 50–51.

52 Hastings Hours: London, British Library, Add. 54782 (fol. 106v); Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 223 (fol. 57v); Voustre Demeure miniatures: Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, 78 B 13 (fol. 4); see Lieftinck, Boekverluchters, vol. 2, pl. 157. The stable roof in Douce 223 was actually derived from another Nativity by Marmion, in the Huth Hours: London, British Library, Add. 38126 (75v); see http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/ FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_38126&index=3. 53 Sixten Ringbom, Icon to Narrative: The Rise of the Dramatic Close-Up in Fifteenth-Century Devotional Painting (Doornspijk: Davaco, 1984), fig. 175. 54 Catalogue of Prints and Drawings . . . from the Northwick Park Collection, the Property of the Late Captain E. G. Spencer-Churchill, auction cat. (London: Christie, Manson & Woods, May 25, 1965), 24–25, lot 127 (illus.). 55 Voelke and Wieck, Bernard H. Breslauer Collection, 98. 56 The Library of Frederick B. Adams, Jr, auction cat., 3 vols. (London: Sotheby’s, November 6–7, 2001), including a biography of the collector. 57 For a reproduction in color, see De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 122 fig. 21. 58 See, for example, the Crucifixion by Gerard David (ca. 1475) in Madrid, Museum Thyssen Bornemisza; see Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 47–48. 59 Voelke and Wieck, Bernard H. Breslauer Collection, 98; Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins & d’Estampes, www.marquesdecollections.fr, no. 522. 60 I have not been able to consult the catalogues of the Gigoux sales, which are listed in Lugt, Marques de Collections, no. 1164. What Gigoux did not sell, he donated to the Musée des BeauxArts et d’Archéologie in Besançon. 61 Voelke and Wieck, Bernard H. Breslauer Collection, 98–99, no. 21 (illus.). 62 For a reproduction in color, see De Kesel, Hours of Queen Isabella, 123, fig. 22. 63 The golden sky is retained in Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256 (136v) and Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 1887 (fol. 58v); other copies contain a landscape and add the figure of Joseph. 64 Karel G. Boon, The Netherlandish and German Drawings of the XVth and XVIth Centuries of the Frits Lugt Collection, vol. 2, Addenda & Indexes (Paris: Institut Néerlandais, 1992), 3–4, pl. 1. The Veltman collection later moved to Bussum, The Netherlands. 65 See Judith A. Testa, “An Unpublished Manuscript by Simon Bening [the Norfolk Hours],” Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1096 (July 1994): 419–21. 66 Krieger, Gerard Horenbout, 10 (Taf. II), 49. 67 The cutting might be attributed to “hand B.” 68 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Douce 220 (fol. 170v). 69 See the miniatures attributed to “Master C” by Dekeyzer, Herfsttij van de Vlaamse miniatuurkunst, 92. 70 Cleveland Museum of Art, Ms 63.256 (fol. 159v). 71 The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms SMC 1 (fol. 271v); see Kren, “The Importance of Patterns,” 370–71; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 132–34, no. 17; Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, “Trivulzio Hours,” in As-Vijvers and Korteweg, Splendour of the Burgundian Netherlands, 218-19, no. 55. 72 See Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, Re-Making the Margin: The Master of the David Scenes and Flemish Manuscript Painting around 1500 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), 148–50. 73 The other option, a Virgin and Child, is used for the “O intemerata” (fol. 95v). Both Marian prayers usually appear in tandem. The Quarré Hours contains the long version of the “O intemerata”; see Gregory Clark’s website Beyond Use: A Digital Database of Variant Readings in Late Medieval Books of Hours at http://arthur.sewanee.edu/BeyondUse/index.php. 74 For the identification of the text, see www.preces-latinae.org/thesaurus/BVM/OPSDMariae. html. 75 See http://manuscripts.org.uk/chd.dk/gui/gks1612_gui1.html. 76 Another leaf may be missing between fols. 120dv (blank) and 121r (containing miscellaneous little prayers). 77 Alternatively, the person who foliated the manuscript in the late seventeenth or eighteenth century made a mistake. This would actually be the most likely explanation if a whole decade were omitted, but both 140 and 150 are extant. 78 The size of this miniature is also different (127 x 92 mm). 79 As noticed by Goehring, “Artist or Style,” 197–204. 80 Paris: Philippe Pigouchet, for Simon Vostre, March 1, 1491–92; see https://archive.org/details/ OEXV360 (digitized copy held by Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Paris: ISTC ih00370000). 81 Paris: Philippe Pigouchet, for Simon Vostre, March 20, 1496, April 17, 1497; see https://archive.org/details/cespresentesheur00cath (digitized copy held by Boston Public Library: ISTC ih00382000). 82 The ISTC (Incunabula Short Title Catalogue), which may be consulted at https://data.cerl.org/ istc, contains a number of editions from this period, but an incunable precisely matching the Quarré Hours could not be found. 83 In the 1496–97 edition the rubric has changed. Several of the other inserted prayers also appear in the two printed Horae. 84 As confirmed by Otto Pächt and Jonathan J. G. Alexander, German, Dutch, Flemish, French and Spanish Schools, vol. 1, Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), 27, no. 362, although the manuscript had been associated with Louis Quarré before. 85 Florence Gombert and Didier Martens, Le Maître au Feuillage brodé: Primitifs flamands; Secrets d’ateliers, exh. cat. (Lille: Palais des Beaux-arts/Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2005), 90–93, nos. 10–11. 86 Fortuné Koller, Au service de la Toison d’or (Les officiers) (Dison: Lelotte, 1971), iii, 70; Félix V. Goethals, Dictionnaire généalogique et héraldique des familles nobles du royaume de Belgique, vol. 1 (Brussels: Polack-Duvivier, 1849), 646–49; Frédéric A. F. T. de Reiffenberg, Histoire de l’Ordre de la Toison d’Or . . . (Brussels: Normales, 1830), 158, 317–18, 331–32. 87 For example, the Munich Hours and a breviary dated 1494 in Glasgow, University Library, Hunter Ms 25; Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 317, no. 89. 88 Kren and McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance, 319–20. 89 Gentleman’s Magazine, May 1832 (published June 1, 1832), 443; according to this report the sale took place April 7–14, 1832. 90 Catalogue of the Splendid, Curious and Valuable Library, of the Late Philip Hurd, Esq. . . . auction cat. (Pall-Mall: Mr. Evans, March 29, 1832) [date differs from Gentleman’s Magazine]: title page, 62, lot 1256. See the New Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts: https://sdbm.library.upenn.edu/, no. SDBM_34573, which can be identified as the Quarré Hours. 91 The description mentions 150 leaves [II+147+I], the size 9.5 x 9 inches (24.1 x 17.8 cm) [I measured 23.7 x 17.8 cm], 12 large paintings [apparently ignoring the calendar miniature, which makes 13] at 8.5 x 5.5 inches (21.6 x 14.0 cm) each [these dimensions include the four-sided borders], and 48 small miniatures [there are 36 (including border scenes): were the large miniatures erroneously counted twice?]: Catalogue of the Splendid and Valuable Library of the Rev. Theodore Williams . . . , auction cat. (Picadilly: Stewart, Wheatley, and Adlard, April 5 and 23, 1827), 104, lot 1030. 92 Giles Barber and David Rogers, “Bindings from Oxford Libraries: II. A ‘Duodo’ Pastiche Binding by Charles Lewis,” Bodleian Library Record 8, no. 3 (1969): 140–41. 93 The binding is in fact an imitation of the late sixteenth-century French Duodo style; Barber and Rogers, “Bindings,” 142–43, pl. xviii. The library of Diana of Poitiers (1499–1566), mistress of King Henry II of France, had been dispersed in 1724; Daniel Leloup, Le Château d’Anet: L’amour de Diane de Poitiers et d’Henri II (Paris: Belin-Herscher, 2001), 62–63. 94 The box is still with the manuscript, but it does not fit anymore, because the pressure in the binding bulged the wooden boards. 95 Heathcote possibly sold the manuscript to Williams through an intermediary called Mr. Farmer: David Rogers, “Francis Douce’s Manuscripts: Some Hitherto Unrecognised Provenances,” in Studies in the Book Trade in Honour of Graham Pollard, ed. Richard W. Hunt, Ian G. Philip, and Richard J. Roberts (Oxford: Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1975): 334. 96 Seymour de Ricci, English Collectors of Books and Manuscripts (1530–1930) and Their Marks of Ownership(Bloomington: Indiana University Press: 1960), 99n2. For the date of Heathcote’s death, see http://incunables.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/record/F-108. 97 See The Arcana Collection, Part III . . . , auction cat. (London: Christie’s, July 6, 2011), lot 20. 98 Rogers, “Francis Douce’s Manuscripts,” 334; Reinhard Kaiser, Der glückliche Kunstraüber: Das Leben des Vivant Denon (Munich: Beck, 2016). 99 Kaiser, Der glückliche Kunstraüber, 335 (citing a letter by Denon from March 28, 1816). 100 Thomas F. Dibdin, A Bibliographical, Antiquarian and Picturesque Tour in France and Germany, vol. 2 (London: Shakspeare Press, 1821): 454. 101 Dibdin, Bibliographical, 462–64. The first manuscript described by Dibdin can be identified as the Dutuit Hours, Ms 36, in the collection of the Musée Petit Palais in Paris, on which see Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, “Livre d’ heures,” in Trésors enluminés de Normandie, une (re)découverte, exh. cat., ed. Nicolas Hatot and Marie Jacob (Rennes: Presses Universitaires, 2016), 219–20, no. 64. The second manuscript seems either French or Flemish and contains the Temptation of Adam and Eve on fol. 45. The third manuscript is Spanish and dated 1553.