Londen, Christie’s Catalogus 7 juli 2010 (Arcana Collection: Exceptional Illuminated Manuscripts, Part I), lot 42 OCTOVIEN DE SAINT-GELAIS (1466/68 – 1502), Epistres d’Ovide

Master of the Chronique scandaleuse

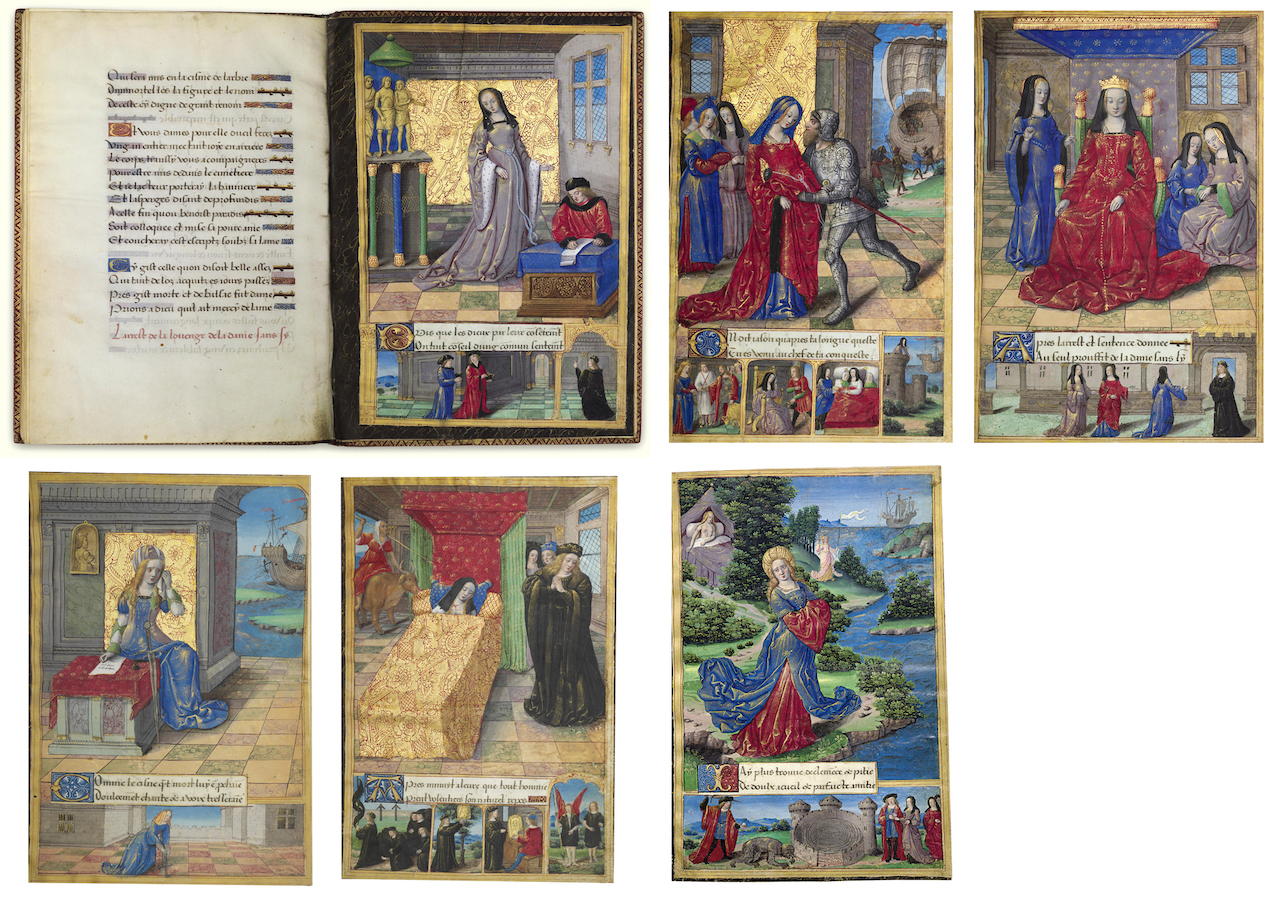

OCTOVIEN DE SAINT-GELAIS (1466/68 – 1502), Epistres d’Ovide, French verse translation of five of Ovid’s Heroides; ?OCTOVIEN DE SAINT-GELAIS or FRANÇOIS ROBERTET (d.1524/30), Epitaphe de Madame de Balsac, L’arrest de la louenge de la dame sans sy, L’appel … contre la dame sans sy, in French, ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT ON VELLUM

[Paris c.1493]265 x 190mm. ii paper + 59 + ii paper leaves: 1of 2, i cancelled, later addition), 2-88, 92, f.59 former pastedown, ends of vertically written catchwords in lower margins of final versos, COMPLETE, 21 lines written in a rounded gothic bookhand in black ink between two verticals and 22 horizontals ruled in pink, justification: 175 x 112mm, titles to final three poems in red, one-line initials in liquid gold on grounds alternately of light blue and maroon, every line with a line-ending either of light blue and maroon patterned with liquid gold or of a knotty branch in brown, later title in red and black on a shield of burnished gold, EIGHT MINIATURES EITHER FULL-PAGE OR WITH PICTORIAL BORDERS IN RECTANGULAR FRAMES OF LIQUID GOLD surrounded by marbling of liquid gold on black and enclosing two lines of text opening with a large initial in liquid gold on a ground of blue or maroon patterned with white (slight wear to margins, some rubbing and cockling to edges of miniatures, faint diagonal crease to miniature f.20, trimmed into frame f.20). 18th-century red morocco gilt with spine in six compartments gilt, title gilt (slight damp staining). Burgundy morocco case, title gilt.A COMPILATION OF VERSES ON FEMALE TRAGEDY AND BEAUTY, THE UNIQUE AND OPULENTLY ILLUSTRATED MANUSCRIPT MADE FOR ANNE OF BRITTANY, QUEEN OF FRANCE

PROVENANCE:

1. The three final poems originated in the court of Anne of Brittany (1477-1514), duchess of Brittany in her own right and Queen of Charles VIII from 1491 to 1498 and then of his successor, Louis XII, from 1499 until her death. In the Appel, the poet visits the Queen, as seen on f.55, when three of her ladies bring the ‘Appeal’ against the ‘Decree’ proclaimed in the Arrest of one woman, probably a poetic fiction, as the Dame sans Sy or ‘Peerless Lady’ of all time. The first lady, Montsoreau, is Jeanne Chabot, dame de Montsoreau; born before 1429 she had served Louis XI’s Queen and in 1492 was one of the senior of the Queen’s ladies; in 1498 she had been joined by her daughter Jeanne de Chambes-Montsoreau, dame de Beaumont. The second, Mombrom, is usually identified as Blanche de Montbéron but is more probably her sister Marie, attendant on the Queen in 1492; there is possibly some confusion in the documents between her and a third sister, Jeanne, wife of Jacques de Chabannes, seigneur de la Palisse. Marie married Geoffroi de Balsac in 1492 and died not long afterwards: it is her death that is lamented in the first poem. The third lady, Tallaru, is Francoise de Talaru, paid in 1492 as one of the Queen’s demoiselles, who married Hugues de Montbardon, seigneur de Villeneuve (Le Roux de Lincy, Vie de la reine Anne de Bretagne, 1860-61; P.-H. Morice, Mémoires pour servir … à l’histoire … de Bretagne, 1742). The volume must postdate the death of Madame de Balsac and the costume supports a dating in the early 1490s, well before February 1497 (n.s.) when Octovien de Saint-Gelais dedicated his full translation of all twenty-one of Ovid’s Epistolae to Charles VIII. The very specific compilation of the Arcana volume was apparently intended for Anne of Brittany herself: it is the only known manuscript copy to combine these texts and the Queen appears in state in the sumptuous miniature on f.55. It is of a luxury and quality appropriate for the library of a Queen who owned books illuminated by the greatest painters of the age.

2. Luis de Mendoça: 16th-century ownership inscription, f.39v and, erased, f.12v; further erased inscriptions on f.59. He also inscribed a copy of a somewhat similar work La complainte de Gennes on a lady supposedly dying for love of Louis XII (BnF, ms fr. 25419).

3. Louis César de la Baume la Blanc, duc de la Vallière (1708-1780), one of the greatest of manuscript collectors: Catalogue des livres du feu M. le duc de la Vallière, II no 2873; he also acquired BnF, ms fr. 25419.

4. ?Jacques-Joseph Techener (1802-1873), the Parisian book dealer, publisher and collector : letter pasted to second paper leaf at front addressed to ‘M. Techener’ and signed ‘la Mésangère’. Monsieur H.D.M.: his sale, Potier, Paris, 23 April 1867, lot 296. Labitte et Voisin, Paris, 20 March 1877, lot 1, see Notice d’un beau ms. orné de huit grands miniatures provenant de la bibl. du duc de la Vallière, dont la vente aura lieu le mardi 20 mars 1877.

5. Charles Stein (1840-1899, famed for his collections of medieval and renaissance art: his sale Paris, 10 May 1886, lot 124.

Bulletin de la librairie Damascène Morgand, 1883-1886, t. III, no 11462.

6. Comte Albert de Naurois (d.1904): his armorial leather bookplate inside upper cover. De Naurois assembled a distinguished collection of illuminated and historical manuscripts; his important copy of Philippe de Commines’s Mémoires, owned by Commines’s niece, was among his manuscripts given to the Bibliothèque nationale de France (n.acq.fr.20960).

Breslauer, Catalogue 109, published on the occasion of the ninetieth anniversary of the firm of Martin Breslauer, New York, 1988, no 9.

CONTENT:

Octovien de Saint-Gelais’s French verse translation of five of Ovid’s Epistolae heroides, letters written by abandoned ladies of myth and mythical history to their faithless lovers, ff.1-49: added title page f.1, no 5 Oenone’s letter to Paris f.2, no 10 Ariadne’s letter to Theseus f.13, no 7 Dido’s letter to Aeneas f.21, no 2 Phyllis’s letter to Demophoön f.32; no 6 Hypsipyle’s letter to Jason f.40.

?Octovien de Saint-Gelais or François Robertet, Lepitaffe de feue ma dame debalsac (heading on f.49v), opening Apres minuyt aleure que tout homme, ff.50-52v; L’arrest de la louenge de la dame sans sy (heading on f.52v), opening Puis que les dieux par leur co[n]se[n]tem[en]t, ff.53-54; Lappel int[er]iecte par telles nommes dedans. Contre la dame sans sy (heading on f.54v), opening Apres larrest et sentence donnee, ff.55-58; ruled blank f.59.

Octovien de Saint-Gelais was a favoured member of the court of Charles VIII who rewarded him with the Bishopric of Angoulême in 1494. He composed original verse as well as translations from Latin: Ovid was followed by Vergil. The combination of five of the Heroides with the contemporary verses is known only from this manuscript and a single print in the BnF from an edition by Jean Trepperel and Michel le Noir of c.1500. Its rarity can partly be explained by the enormous popularity of Saint-Gelais’s translation of all twenty-one letters, known in at least fourteen manuscripts, many luxuriously illuminated, and in numerous printed editions. The subject matter, the heroines of antiquity relating events from their, female, perspective, might have encouraged Saint-Gelais to offer his first translations to the Queen, whose own life was just as dramatically at the mercy of men. Heiress of Brittany, she was forced to marry Charles VIII and agree that, if widowed, she could only remarry his successor.

These five letters are among the most tragic and so have some connection in mood with the lament for Madame de Balsac. Otherwise, there is no real connection in theme, perhaps an argument for St Gelais’s authorship of at least the first of the three following poems. The poet of the Epitaphe says that he will carry a banner in the funeral procession — ie lacteur porteray la banniere — and so can be identified as the man dressed in black with a small coronet around his hat, seen also at the deathbed above, f.50. His coronet perhaps distinguishes him as prince of a court of love — madame de Balsac is la maitresse et dame des amants, while the language and usage of the law court underpins the other two poems. Alternatively, he might be prince of a rhetoric chamber or literary association. Comparison with Anne’s crown on f.55 makes it most unlikely that the coronet indicates the King, who is referred to in the final poem as though he were not one of the protagonists. The coroneted figure reappears in the following miniatures, ff.53, 55, but is not necessarily the poet of the other two poems, which explicitly claim a single author. In the Arrest, the author refers to himself as the secretaire, presumably the figure in red engaged in writing, a person distinct from the prince who will pronounce judgement, presumably the coroneted figure, f.53; in the Appel, the author is distinct from ’the royal lover in black livery’ who will arbitrate, presumably the coroneted figure, f.55. If the artist has correctly interpreted the texts, this suggests that the author of the Epitaphe (?Octovien de St Gelais) is not the author of the Arrest and Appel. The author(s) are probably among those named in the Arrest: Saint-Gelais, and two other poets, Guillaume Cretin (c.1465-1525) and François Robertet, together with Pommer or Pomnier and Bremont, who have yet to be identified (f.53v): Robertet is often advanced as the author of the final two poems.

These three poems seem intended for an exclusive, privileged audience and so achieved a very limited circulation. They are found together, without the Epistres, in one other manuscript, with only one of its three original miniatures remaining, which is bound with a print of the Chevalier delibéré, a meditation on death from the court of Burgundy (BnF, Rés. vélins 2231); the Arrest appears alone in a manuscript compilation (BnF, ms fr.2206), see Droz.

ILLUMINATION:

The magnificent miniatures are by the Master of the Chronique scandaleuse, named from the copy of Jean de Roye’s chronicle in Paris (BnF, Clair. 481), who was earlier referred to as the Master of Jean de Bilhères from the book of hours he illuminated for the Abbot of St Denis (BnF, lat. 1071; for the Master, see Avril and Reynaud, pp.274-7). His activity can be traced in Paris between about 1490 and 1510 when he attracted commissions for the greatest patrons: the Epistres d’Ovide was selected to represent contemporary Parisian illumination in the exhibition Jean Poyet: Artist to the Court of Renaissance France held at the Morgan Library, New York, in 2001 (see Wieck). In 1504-1505 the Master illustrated for Anne the account of her second coronation (Rothschild Collection, Waddesdon Manor Ms 22). For the copy of the Golden Legend, specially printed by Antoine Vérard for Charles VIII in 1493, he provided a grand frontispiece where the King, with large crown, kneels before the company of heaven with his Queen and her ladies in the bas de page below. The correspondences in design and costumes confirm the dating of the Arcana volume, as does the very similar technique of rapid assured brushstrokes and lavish use of gold for highlights and patterning. The Master often collaborated with other artists and a hand closer to Jean Pichore may have worked on some of the border scenes — Jean Pichore himself drew on the compositions of Oenone, f.1, Dido, f.21, and Ariadne, f.13, for the copy of the full translation that he illuminated for Louise of Savoy, the mother of Francis I (BnF, fr.873, see C. Zöhl, Jean Pichore, 2004, p.190).

The Pichore manuscript is unusual in emulating the ambition and variety of the miniatures of the Arcana volume. Generally in copies of the complete Epistres d’Ovide, the ladies, seen at half- or three-quarter-length, simply write their letters with no reference to their stories as, for instance, in the copy in the Huntington Library, HM60, which has been asociated with Anne of Brittany and Louis XII from the mistaken identification of their portraits in two of the miniatures. Although in the Arcana volume Oenone, Dido and Phyllis are shown with paper or parchment before them, much more is conveyed than their scribal activity through the marginal or subsidiary scenes, ff.1, 23, 32. No letters appear with the emotive figures of Ariadne and Hypsipyle, whose resigned acceptance of Jason’s departure, f.38, throws into relief the despair of Ariadne, whose twisting figure with tossing draperies conveys her anguished attempts to signal to Theseus and her terror at discovering their futility, f.13.

All the miniatures would have required precise instructions, particularly so when they contain details not in the text as for Oenone f.1, and Phyllis, f.32. The close involvement of the author(s) in devising the illustrations would be expected for the first, presentation, copy. Complex visualisations were very much to contemporary taste: the Master of the Chronique scandaleuse provided the symbolic miniatures for perhaps the most famous example, the Enigmes of Pierre Sala (BL, Stowe 955) around 1505. The Epistres d’Ovide shows his style at its most careful and elaborated, with smoothly modelled faces and a splendid use of gold and rich blues and reds. The importance of the commission encouraged the artist to create an exceptional manuscript, truly worthy of a queen.

The subjects of the miniatures and pictorial borders are as follows:

f.1 Oenone, abandoned by her husband Paris, writes of her grief as his ship sailed away, at the right, to bring Helen to Troy as his wife. The marginal scenes, from the top, provide the background: Hecuba dreams that she gives birth to a flaming torch; the seer Aesacus interprets this as foretelling Troy’s destruction and, on the day of Paris’s birth, that the child born that day will fulfil the prophecy’ and so must be killed; instead, Paris is given to Priam’s herdsman to be exposed on the mountains; after nine days the herdsmen finds the baby still alive and rears him; Paris and Oenone with their son Corythus; in the only direct illustration of her letter, Paris and Oenone content as shepherd and shepherdess together, Paris turning to the trees perhaps to illustrate her recalling how he carved his love for her onto tree trunks.

f.13 Ariadne distraught on Naxos as she sees Theseus’s ship sail away, with other scenes from her reproachful letter: to the left background how she woke up in bed to find she was alone, also alluding to how she returns to their bed to lament his absence; to the right how she tied a white garment to a branch to signal to his ship, seen departing on the right. Below are her generous deeds that Theseus’s ingratitude makes her regret: on the right, she gives Theseus the ball of thread that he will unroll to find his way back through the labyrinth, in the centre; to the left, he kills the delightfully gold-furred Minotaur.

f.21 Dido, as told in the letter under her hand, drops tears on the sword of Aeneas, whose ship is sailing away to the right; she does not wish to forget him and so his portrait, as King Consort of Carthage, hangs on the wall. Below, as she has declared, she kills herself with his sword.

f.32 Phyllis, accompanied by two ladies, writes to Demophoön, who has failed to return from Athens to marry her; she haunts the Thracian shore looking for his ship but the only visible vessel is one departing to signify her abandonment. Below the text, but within the same landscape, the small figure of Phyllis hangs from a tree, her means of suicide more clearly predicted by Saint-Gelais than Ovid to anticipate her metamorphosis into an almond tree when Demophoön finally comes back, a fate also suggested by her careful alignment with a thicket of trees in the miniature.

f.38 Attended by three ladies, the pregnant Hypsipyle is given a farewell embrace by Jason, who rests his hand over their unborn child — Hypsispyle recalls in her letter that he pledged they would be parents together; he is the last to join the Argonauts embarking on the Argos, in the background, to search for the Golden Fleece. Below, from right, are scenes related in her letter: she climbs a tower to keep the Argos in sight for as long as possible; she gives birth to twin sons; a traveller brings news of Jason’s perfidy; Jason, holding the Golden Fleece, marries Medea.

f.50 Madame de Balsac on her deathbed: from the left Atropos riding on an ox — a motif ultimately derived from Petrarch’s Trionfi — has speared her in the neck, on the right the lamenting poet dressed in black, with a coronet in his hat, perhaps as a Prince of Rhetoricians or Prince of a Court of Love. Below, from the right, in their order within the poem: Cupid, with blindfold and arrows, is dressed in mourning, with a man similarly dressed, perhaps one of those languishing under his rule; Zeuxis responds to the coroneted poet’s plea that he paint Madame de Balsac’s portrait; the coroneted poet places it in the tree of immortelles; the coroneted poet, carrying the banner, leads the funeral cortège into the cemetery.

f.52 The Peerless Lady stands before a cloth of gold, on the left the statues of three gods on a raised platform, representing the tribune of the gods who declare her to be without peer, on the right the author, as secretary, writing down the decree. Below, the coroneted figure in black of the previous miniature raises his hand, perhaps the Prince of the final verse proclaiming the decree, as two men approach with books, perhaps two of the five who have searched out the evidence for the court: Pommer or Pomnier, Cretin, Robertet, Octoviam [sic, Saint Gelais] and Bremont.

f.55 Anne of Brittany enthroned with three of her ladies, Montsoreau, Mombron and Talaru, who appeal against the judgement proclaiming the status of the Peerless Lady. Below, the three ladies approach the coroneted black figure of the previous miniatures, who should here be the amant royal portant livree noire to whom the author and the ladies agree to submit for arbitration.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR THIS MANUSCRIPT:

E. Quentin-Bauchart, les femmes bibliophiles de France, II, 1886, pp.380-2.

H.J. Molinier, Essai biographique et littéraire sur Octovien de Saint-Gelays, 1910, reprinted 1972, pp.144-5

E. Droz,’Notice d’un manuscrit ignoré de la Bibliothèque nationale’, Romania, XLV, 1918-1919, pp.509-10.

F. Avril and N. Reynaud, Les manuscrits à peintures en France 1440-1520, 1993, pp.276-7.

R. Wieck, ‘Post Poyet’, pp.247-263 in Excavating the Medieval Image, Manuscripts, Artists, Audiences, Essays in Honor of Sandra Hindman, D. Areford and N. Rowe eds, 2004, p.248.

C. Brown, ‘Celebration and Controversy at a Late Medieval French Court: a Poetic Anthology for and about Anne of Brittany and her Female Entourage’ (forthcoming)